Against the Wall

Good fences make good neighbors. But walls often signal fear, hatred, oppression.

Read

This season we’ve adopted walls as our loose theme, and architectural historian Louis Nelson joins Will and Siva to help frame the idea. At the University of Virginia, wavy brick walls enclose beautiful gardens. But as Nelson explains those walls once served a more sinister purpose. Drawing on this lesson from the past, our guest and hosts grapple with the meaning and function of walls in a democracy — along borders, in cities and in people’s hearts and minds.

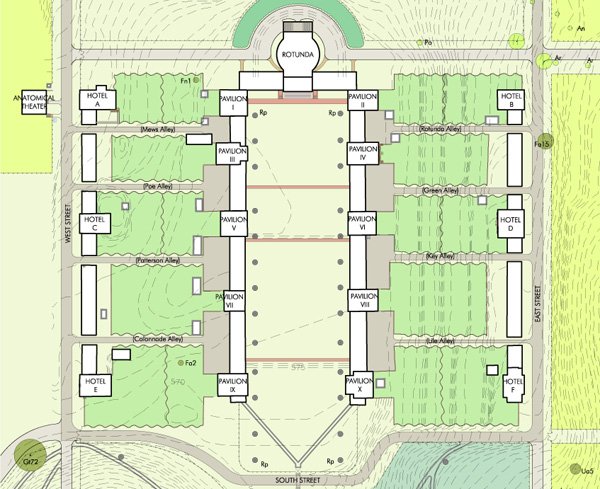

Now a UNESCO World Heritage site, UVa’s celebrated Academical Village was designed by Thomas Jefferson and built with the labor of enslaved people. The campus features an expansive, terraced lawn with housing for students and faculty on either long edge. And behind that housing, Jefferson erected curvilinear walls around a series of “gardens” — where the working world of slaves took place, out of plain sight. Today they are lauded as actual gardens, with manicured flora tended by relatively low-wage workers.

Nelson connects this past effort to shield from view the unseemly features of American democracy to contemporary issues: like the U.S. southern border, memories of the Berlin Wall and the massive barriers that isolate the Gaza strip from the state of Israel.

Meet

Louis P. Nelson is a professor of architectural history and the University of Virginia’s vice provost for academic outreach. He’s the author of Architecture and Empire in Jamaica (2016, Yale University Press) and The Beauty of Holiness: Anglicanism and Architecture in Colonial South Carolina (2008, UNC Press). His research focuses on the early modern Atlantic world, especially the American South, the Caribbean and West Africa. Nelson is co-editor of a forthcoming volume on how space was organized around slavery in the Academical Village. And he leads a university commission working on memorializing UVa’s history of slavery.

Nelson has also participated in an international project including African and American scholars to preserve historic slave sites in Senegal.

In an essay about the Jan. 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol, Nelson argued for conserving samples of the destruction left behind. “The shattered doors and the broken glass remind us that Constitutional stability is not promised,” he wrote. “To preserve the physical legacy of this most recent chapter of the building’s — and America’s — history gives both legislators and millions of visitors a potent reminder of the dangers of forgetting.”

Nelson has been a leading voice in contextualizing historical monuments in Charlottesville, Va. Besides serving on a renaming commission for the university’s memorials and the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University, he has written in Site/Lines about UVa’s Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, which was completed in 2020.

Learn

UVa’s serpentine walls caused a stir in the collegiate athletic world in 2020. Officials scrapped changes to the Virginia sports logo that alluded to the walls.

Building a 450-mile border wall was a core element of the agenda of Donald Trump, who boasted that Mexico would somehow pay for it. Today, the former president is leaning into that old rhetoric in his bid for another term. The Washington Post reports that Trump and his political allies are considering using the military to detain and deport migrants.

There is no question that huge levels of migration are straining the U.S. immigration system. And Latin Americans aren’t the only people crossing the border. Last year, Chinese citizens took that journey in record numbers, making them the fastest-growing population of migrants crossing the southern border.

Walls of course aren’t all material. In China, the Golden Shield Project — more commonly known as the Great Firewall — regulates access to the internet and censors content. The recent explosion of artificial intelligence presents challenges to this system, according to the Economist.

Geographic features create natural borders, but even those get wrapped up in human circumstances and symbolism. In his forthcoming book Border of Water and Ice, environmental historian Joseph Seeley writes about the Yalu River between China and Korea and its significance during the time of Japanese imperialism.

Israeli leaders built what they call a border fence to seal off Gaza. In 2021, the Israeli defense minister acknowledged that enhancements to the fence had created in effect an “iron wall,” including underground fortifications, cameras, radar and other surveillance technology.

These efforts did not prevent the deadly assault carried out by Hamas on Oct. 7, which Israel has responded to with a crushing invasion of Gaza. Now Egypt is building its own buffer to control the flow of thousands of Palestinians trying to flee.

Border walls can come down, if the conditions are right. The Berlin Wall stood for 28 years during the Cold War, dividing the city between east and west. Today its remnants are potent voices of historical memory.

Transcript

Democracy in Danger S8 E2: “Against The Wall”

[THEME MUSIC]

[00:03] Will Hitchcock: Hello, I’m Will Hitchcock.

[00:04] Siva Vaidhyanathan: And I’m Siva Vaidhyanathan.

[00:06] WH: And from the University of Virginia’s Karsh Institute, this is Democracy in Danger.

[00:11] SV: It’s been a while, Will. It’s good to see you.

[00:13] WH: Good to see you, too, Siva. We missed you last time for our conversation with Emily about China and the reshaping of its collective memory around World War II. You would have loved that. We talked a lot about movies, too.

[00:23] SV: Yeah, you know, I had a chance to catch up with that episode. It was really great. And you know, look, one of the things that struck me is how official stories about the past can put up blinders to our thinking. They make complex events seem way too simple. It’s like people want to erect these ideological walls sometimes to protect themselves from nuance, from hard and honest conversations, and maybe from some guilt.

[MUSIC FADING OUT]

[00:49] WH: So, Siva, you mentioned the word walls, and this is an idea that you have been urging us to kind of embrace as a theme for the coming season.

[00:56] SV: Yeah, I’ve been thinking a lot about walls recently. Of course, they function as boundaries, you know. They function for the purpose of safety, but often for exclusion. And look, physically, they keep people out or they keep people in. And, metaphorically, the walls in our minds, right — the ideological walls — they police our very ideas. They influence what we can and should think about.

[01:22] Now, walls aren’t necessarily bad. We need them in our lives, but they’re a particular challenge to an inclusive democracy, because in some cases walls can be a barrier to the flow of the very values that democracy needs to stay alive.

[01:42] WH: That’s exactly right, Siva. And really there’s no better way to begin a reflection on walls — and their various meanings for our politics, our democracy — than with a scholar of architecture who’s thought a lot about exactly these issues right here at the University of Virginia.

[01:56] SV: Yeah, we’ve invited our colleague Louis Nelson to join us in the studio today. Louis is an architectural historian whose books on buildings and landscapes in the Atlantic world have won numerous awards. He also chairs a university commission that’s been taking a hard look at how we acknowledge, memorialize and address UVa’s history of slavery.

Louis, welcome to Democracy in Danger.

[02:20] Louis Nelson: Thanks so much, Siva. Thanks, Will, for having me here. It’s a delight.

[02:23] SV: So, Louis, you know, Thomas Jefferson founded this university, and he designed this Academical Village that sits in the center of it. For those who have not seen it, what is it like, what is it about, and why is it so important? Why is it so lauded?

[02:41] LN: Yeah. Let’s begin just simply with the fact that it’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site tied to Monticello. So it is widely recognized as contributing to world heritage. That’s really pretty significant. But for many of your listeners that haven’t been to the University of Virginia, let’s actually set the stage.

[03:00] So the complex of buildings designed by Jefferson and erected by enslaved laborers over the course of a decade, in the early 19th century, are largely organized in the shape of a U. At the head of that U is a capstone building, which we refer to as the Rotunda. It’s a round building with lots of columns. All the buildings at UVa in this early period have lots of columns. But that round building functioned as a library, and it’s really the capstone of the U. Extending from that will be two parallel arms. Each of those arms has five buildings on either side, so a total of 10, creating this contained space that we refer to collectively as the Lawn. Those arms — each with five buildings on either side — those five buildings are referred to as pavilions. And the pavilions were designed by Jefferson and intended to house each one professor. The professor upstairs in his apartment with he and his family, and then downstairs would be the classroom.

[03:53] Jefferson had determined, at the outset of the university, that there were either nine or 10 — depending on which list you’re looking at — nine or 10 useful domains of knowledge. And, especially, specifically for the training up of citizens into democracy. All of those 10 schools, then, coming together to create the Academical Village that is the University of Virginia.

[04:14] SV: So the Academical Village is just like faculty and student housing, right? It’s really nothing more than that, right?

[04:19] LN: Well, no, of course not. Jefferson, quite smartly, designs the Academical Village on a naturally occurring ridgeline. When you walk through what we refer to as the Lawn, you experience this as three flat terraces. Jefferson didn’t happen to find the only three perfectly flat terraces in Albemarle County. It’s a manipulated landscape. And the only way you can create that is by having the architecture that I just described function as a retaining wall to hold up the earth on either side of that manipulated flat terracing. Well, what that means is that the topography on either side of the lawn descends in both directions.

[04:57] And so, I was a little misleading, in fact, when I told you that the Academical Village was simply just a U. That assumes two arms — it’s actually four flanks. Right, there’s the two flanks that are the pavilions. And if we think about those as flanks two and three, what I didn’t mention is flank one and four. And those are both at the bottom of the hills, cascading down those hills, and those are dominated by a second type of building called the hotels. And those hotels would have provided the hoteling services: both accommodations and meals, as well as cleaning services for all of the students that are resident at the Academical Village. And today, the spaces between those registers, those flanks, are beautiful gardens filled with azaleas — especially in the spring — there are tulips and azaleas, magnolias, they’re really spectacular spaces. And so, it is today experienced as a beautiful landscape.

[05:47] WH: Well, when I first came to the University of Virginia to join the faculty, one of the first places that I went was to the gardens behind the pavilions, because they’re absolutely stunning. They’re small spaces bounded by these fascinating, wonderful, historic curved walls. But, of course, this was a site of enslaved people producing food and value for the university itself. Just talk a little bit about the way in which it was designed around the labor of enslaved people to serve the university and the students.

[06:17] LN: Yeah. We often talk about the architecture of the Academical Village as surviving remarkably intact, largely unchanged from its early 19th-century condition. Which makes for, you know, geeks like myself really interested in the history of architecture — there’s a lot to talk about. But what that masks is this sense that in fact the entire landscape is also preserved intact. And that would not be true. So those gardens that you found so charming, Will, when you first came to the University of Virginia — those are all installed in the mid–20th century, late 1940s and 1950s. But what they replaced was something utterly different.

[06:54] So those yards — the spaces behind the pavilions and between the pavilions and the hotels — were originally filled with chicken coops, with kitchens, with laundries, with all the things that were necessary to support the infrastructure and the everyday life of an elite white household in antebellum Virginia. There is an entire cadre, a whole community, in fact, of enslaved individuals at the opening of the university, almost 1:1, that are housed here at the University of Virginia and that are shaping those spaces.

[07:28] And then in the 1940s and the 1950s, the ladies of the Garden Club of Virginia come in and quote-unquote “reconstitute” Jefferson’s original colonial gardens, which, of course — they’re imagining pleasure gardens, not actually the landscapes that families of enslaved, and enslaved children, labored in for a half century.

[07:48] SV: Now the walls that encompass these gardens, did they obscure that labor from passersby? Was there a sense that we weren’t supposed to acknowledge that? Or, because even today, of course, we’re not supposed to acknowledge it.

[07:59] LN: Yeah, this requires some nuance to really understand. The garden walls, which are serpentine, or curvilinear, were remarkable in their moment in early America. There were very few curvilinear walls, and they’re quite remarkable today. People love the curvilinear walls. But what we have to understand is that the curvilinear walls that we experience today were all installed as part of that 1940s and 1950s program. Not one of those curvilinear walls is one of Jefferson’s walls.

[08:29] And so, as we have gone back to the archives and understood the construction accounts and the records and the use of the archeological record to better understand, well, what were Jefferson’s curvilinear walls today? They stand at about 4, 4 and a half, feet tall. They were originally 8 feet tall. And so that means that they’re experienced very differently in the 19th century than they were when they’re reconstituted in the early 20th century. In the early 20th century, we experienced them as beautiful dividers of a viewshed cascading from garden to garden.

[09:00] So, Jefferson doesn’t have some presupposition that he can actually pretend that this is an enslavement-free landscape. So, he’s not hiding. He’s separating. And this is one of the things that we have to think about as you’re continuing with this series, how do walls function? Siva, you gestured to this. You have walls of exclusion, you have walls of containment and you have walls of separation. And I think Jefferson, here, is deploying this idea of wall of separation. And that’s not necessarily fully containment. But why would you seek to separate? Well, it’s because Jefferson actually is prepared to say that slavery is a corrupting force in democracy. He writes about the deleterious effects of slavery in his Notes on the State of Virginia. So, on some ideological level, Jefferson is prepared to say slavery is a moral ill.

[09:58] I think I’d like to make one more point here, again sort of grounded in the early 19th century. And that is, when Jefferson creates a wall of separation between white male students and enslaved black laborers, he does so based on emerging theories of natural philosophy that presuppose a hierarchy of the races. So that physical conditions, physical expressions of race, are inextricably bound to intellectual and moral capacities. And so, people of color can’t be citizens because they don’t have the intellectual and the moral capacity to perform as a citizen. Of course, that’s completely false. Right, let me just be really clear. There’s no science.

[10:38] SV: That’s still widely accepted, unfortunately.

[10:40] LN: But that bias found in the early 19th century continues to shape our imaginations.

[10:45] SV: And our policies.

[10:46] LN: And our policies. Right. But then, how should that actually function? Let’s think about what UVa is intended to do. UVa is designed by Jefferson to graduate students into moral, democratic leadership. His curvilinear walls, then, are designed to create this separation between white, enlightened pursuit of freedom and the black condition of being constrained into a condition of slavery.

[11:14] SV: You could also say, separates the matters that are corporeal from the matters that are cerebral.

[11:18] LN: Ah, so good.

[11:19] SV: Because if it’s food and waste going on behind the walls and in the alleys between as students go to their classes, right, it’s much more to be liberated from the concerns of the corporeal.

[11:31] LN: That’s exactly right. That’s exactly right.

[11:33] WH: Louis, it sounds like you and Jefferson are both working on this theme that space, and the way it’s designed and the way it’s used, matters — for learning, for cultivating a certain civic attitude, for democracy itself. We have different visions of what democracy should be than Jefferson did. But nonetheless, there is a democratic impulse behind the design of the university, just as there is in our contemporary life. Architecture matters for our politics. What do architecture historians have to say about that in the contemporary sense? What’s the relationship between the practice of democracy and our built environment?

[12:10] LN: I think there’s a direct correspondence. And that is that our landscapes shape our imagination for who we are, even as we then shape the future landscapes we seek to occupy. So, for example, after the events of January Sixth, I wrote an op-ed specifically arguing for the necessity to preserve some of the damage of that impact on the Capitol, so that future generations of Americans visiting that space be confronted with the collapse of democratic principles in that moment. When our bodies are confronted with the material evidence of democracy’s collapse, we then are confronted with, “Whoa, what’s my role right now as an individual — and as a collective — in seeking to repair and preserve that?”

[13:02] SV: So we should leave a scar.

[13:04] LN: Absolutely.

[13:04] SV: The way that pieces of the Berlin Wall stand in the middle of Berlin.

[13:08] LN: Absolutely. No, that’s exactly right.

[13:12] SV: Well so, extending this wall thing, right. We’ve just gone through a period, and we might be in a period again, where “Build that wall!” is a rallying cry for Americans. But what does it say to you when you hear that phrase — as someone who cares about democracy and thinks about walls — what does that invoke for you?

[13:31] LN: It actually evokes a direct correspondence between our contemporary discourse around that southern wall and the kinds of predispositions that Jefferson had when he is building out the University of Virginia. There’s a direct line between these. And that is that the wall — the southern border wall — is a material manifestation of our naturalization or immigration policies.

[13:54] And so, when we actually take just a quick survey of those naturalization and immigration policies, we come to realize that even in 1790, the drafters of the new naturalization clauses are arguing that only free white people of good moral character can become citizens. Right. And then when we think about the 1880s Chinese Exclusion Acts and in the 19-teens and 1920s immigration acts, which are specifically designed to exclude southern Europeans and eastern Europeans, we come to recognize that our immigration policy — that the wall on the southern border — is nothing more than the long historic arc of Americans’ preferences for whiteness as the marker of American citizenship.

[14:42] SV: So is the chant “Build the wall!” actually stronger than the mythical wall?

[14:48] LN: Oh, absolutely. I mean, this is where we — you spoke to the Berlin Wall a few moments ago — this is where we have to understand that walls in our imagination and the real walls in the landscape are not necessarily always coterminous, but they’re always in dialogue. Right. The Berlin Wall has come down, but it was a line on a map before it was a wall. So it was a partitioning, it was a political idea, before it became barbed wire, before it became a concrete wall.

[15:15] It then opened the imagination for folks on both sides of the Berlin Wall to say, “Oh, the wall doesn’t exist anymore.” The physical wall still exists. But the wall of separation, which the physical wall physically reinforces but also — in the imagination of the body politic — insists upon, that imagination eroded. In a night. And then for the next year, the physical legacy of that was taken down. And we have thousands of examples across the world of people who have a chunk of concrete on their mantel. So, the wall, the potency of the Berlin Wall, survives. It has political power in the imagination of many people.

[16:01] SV: Even in the negative now.

[16:02] LN: Even in the negative.

[16:03] WH: A cautionary tale. But let me just run with this a little bit. I mean, are national borders bad? There is something to be said for delineating the nation-state, and it’s perfectly okay to have an immigration policy as to who can come in and who can go out, who is a citizen and who isn’t. Nations have been doing this, in a way that is humane and fair and just, and they’ve also been doing it in ways that is very inhumane and unjust. But, the question of policing a national boundary is open for debate. It’s open for discussion. Just because you want to have a border that you can identify and call your own doesn’t turn you into a criminal, does it?

[16:46] LN: No, but I think it does speak to the moral condition of the citizenry bounded within that state. Right. And that is when a citizenry who enjoy privilege refuse to release their grip on that said privilege, then the boundaries of that state, that nation-state, must be more rigorously policed. And so I’ll take your point, Will, that policing is necessarily going to happen. The question is how intense is that policing, and what are the both the policies and the biases that undergird that particular policing? We’re very happy to let immigrants from some places in the world right into the United States, and we’d rather not have immigrants from other places come into that world. Right. So it’s not just a question of the permeability of the border, but it’s actually about who our hearts desire to have as neighbors, and, whence they’re here, am I prepared to release my grip on my own privilege to share the bounty of democracy with those new-coming Americans?

[17:46] WH: Yeah, that’s very well put. And it’s worth also reminding our listeners, I mean, before we romanticize the fall of the Berlin Wall — Europe has borders. I mean, the Berlin Wall may have fallen. Yeah, the two Germanys have been reunited, and many other national boundaries have been made porous or even nonexistent inside Europe. But, boy, Europe itself has borders, and they have a huge public disagreement about how to quote-unquote “police” those borders. So borders haven’t disappeared, they just get moved from time to time.

[18:15] LN: That’s right. And they’re stronger for some people than they are for others. That’s the piece I would just really want to reinforce, right. Germany is having a robust conversation about immigration right now, and it is motivated in part by the types of people that seek to become Germans. Can they be Germans? And we would ask the same question of America. Can those nonwhite people be Americans?

[18:38] SV: Right, right. So when walls that represent an ideology or represent a sense of bigotry actually become real and exist in our world, do they have a reifying effect on that ideology? Because I think about fervent argumentation about the construction of fences and walls between Israel and the occupied territories of Palestine. And there was this weird debate where people in Israel called it a fence and people in Palestine called it a wall. And, like, what kind of argument is that? But there were stakes attached to that, right? What is that path from the walls of our minds to the actual walls in the world, and what does that do to us? Does it make it that much harder to recoil from that?

[19:23] LN: Yeah. I do think the physical manifestation of the wall that marks the previous policy, public imagination of some kind of separation, makes it much harder to then render permeable, shift and deconstruct that wall. And that only really effectively happens, of course, if it’s welcome on both sides. This is what made the deconstruction of the Berlin Wall so effective. It was a welcome deconstruction on both sides. But I do think that it’s important to recognize that when you get to the moment — the physical presence, the construction of concrete and barbed wire and steel — that cements in the imagination, the public imagination, the popular imagination, immovability, permanence. And so it requires an extraordinary imagination to reach past that.

[20:17] Israel refers to “fence.” Palestinians refer to “wall.” I think we should just distinguish between how fences and walls operate. Walls are hard, impermeable divisions. A fence is a marker of a boundary, but a fence assumes a mutually agreed upon social contract, right. We think of fences as making good neighbors. We say that all the time in America, right? “Good fences make good neighbors.”

[20:46] WH: Robert Frost.

[THEME MUSIC FADING IN]

[20:47] LN: That’s right. There’s a transparency to a fence that allows holding one’s neighbors, or a commitment of myself to a certain standard of well-being, of flourishing, of bounty in that particular space. “I’m maintaining this. There’s beauty here. There’s flourishing in this space. And when I don’t do that, you can see that through the fence.” To have the same boundary called fence on one side and wall on the other actually bears profound political, social-political, consequences.

[21:18] SV: Louis Nelson, thank you so much for joining us on Democracy in Danger.

[21:23] LN: Thanks so much for having me. It’s been a lot of fun.

[THEME MUSIC FADING UP]

[21:35] SV: Louis P. Nelson is a professor of architectural history here at the University of Virginia. He’s also the vice provost for academic outreach. His most recent book is Architecture and Empire in Jamaica, widely regarded as a tour de force in his field.

[21:51] WH: Democracy in Danger as part of The Democracy Group podcast network. Visit democracygroup.org to find all our sister shows. We’ll be right back.

[MUSIC FADING OUT]

[22:13] WH: Siva, listening to Louis, I was thinking about a scene that I often play at the end of my Cold War class, which is Ronald Reagan standing in front of the Berlin Wall saying, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” The idea is that Americans think of themselves — we think of ourselves — as not liking walls. Walls are bad. Walls inhibit freedom. They inhibit trade. They inhibit capitalism. They inhibit ideas. But honestly, Americans love walls, and we are surrounded by them. And since the 18th century, we’ve been building legal as well as physical walls to keep people out, to only allow certain kinds of people in.

[22:46] You know, one of Reagan’s political contemporaries was Pat Buchanan. And Pat Buchanan started his political career running for president in the early 1990s by giving his first speech on the southwestern border, saying, “Build a wall!” And this is the very dilemma and duality of our politics: We say we don’t like walls out of one corner of our mouth, but boy, we love them out of the other corner.

[23:09] SV: Sure thing. I mean, look, another part of the big American mythology or ideology of the 19th century was “no fences,” right, that ranchers were fighting fences and driving cattle across land with no barriers. Right. That’s part of the American mythos of expansion. Unexamined in that is the slaughter of millions of people who actually occupied that land at the time. But that’s the thing. We have a mythology of living without walls and living beyond walls and tearing down walls. But, in reality, we have always put up walls — to imprison, to encompass and to protect. And let’s remember that while the United States has two long borders, peaceful borders, we also have two big moats that have largely isolated us from the turmoil of the rest of the world, except when we choose to be a player in that turmoil.

[24:10] WH: No, and one thing to remember, as you mentioned, about the pioneering spirit — “Oh, we’re gonna, you know, the West is open, it’s free, there’s no people there” — is of course, this was also a gigantic project of creating new walls for Native Americans who lived in North America, who then were herded into reservations. So —

[24:28] SV: Concentration camps.

[24:29] WH: If you like. And, you know, here we are once again, we’re reflecting, I think it’s the 70th anniversary of Franklin Roosevelt’s executive order to put people of Japanese origin or descent into concentration camps in 1942. So, I think this is a great theme for us to play with. You know, we often talk about our politics now being divided into these political sides that just have steep and increasingly impenetrable walls between them. And it feels suffocating at times. It feels like we can’t even see across the wall to observe what’s really happening, you know, on the other side. I think, metaphorically speaking, walls are bad for our democracy, they’re bad for our own sense of identity, our own sense of civic virtue.

[25:15] SV: Right, right. Definitely, these invisible ideological walls are limiting our sense of common trust and mutual recognition of humanity, all of those things. And so we should be focused on what walls we want to tear down, what walls we want to stop from being built, but also look around the world at the history of walls and the ways in which walls have kept people apart too well and sometimes failed in their jobs. Right, so a lot of the walls we look at historically turned out not to be that effective.

[THEME MUSIC FADING UP]

[25:47] WH: Mr. Vaidhyanathan, tear down this wall!

[25:49] SV: Right, right.

[THEME MUSIC FADING UP]

[26:00] SV: That’s all we have for this episode of Democracy in Danger. Next time we’re taking another look at America’s tragic, destructive culture of guns.

Jennifer Carlson: You know, when we talk about what’s going to happen to the NRA, I think it’s those deeper cultural currents that the NRA has shaped that are going to be the most lasting and significant.

[26:18] WH: In the meantime, catch up on anything you’ve missed. Visit our webpage, dindanger.org. Browse our extensive archive of 100 episodes, and leave some comments on what you read and see.

[26:29] SV: And visit us on social media. We’re on Instagram @dindpodcast. That’s D-I-N-D podcast. There, we’re going to be posting reels from behind the scenes of our production studio, and soon much more on upcoming episodes.

[26:42] WH: Democracy in Danger is produced by Robert Armengol, Nicholas Scott, Stephen Betts and Ariana Arenson. Adin Yager engineers the show. Our interns are Charlie Burns, Leena Fraihat, Katie Pile, Makhdum Mourad Shah, and Caroline Yu. We have help from Ellie Salvatierra.

[26:59] SV: Support comes from the University of Virginia’s College of Arts and Sciences. The show is a project of UVa’s Karsh Institute of Democracy. We’re distributed by the Virginia Audio Collective of WTJU Radio in Charlottesville.

I’m Siva Vaidhyanathan.

[27:15] WH: And I’m Will Hitchcock. We’ll see you soon.

[THEME MUSIC OUT]